Swayambhu Puraṇa Comprises the Emergence of the Swayambhu Stupa

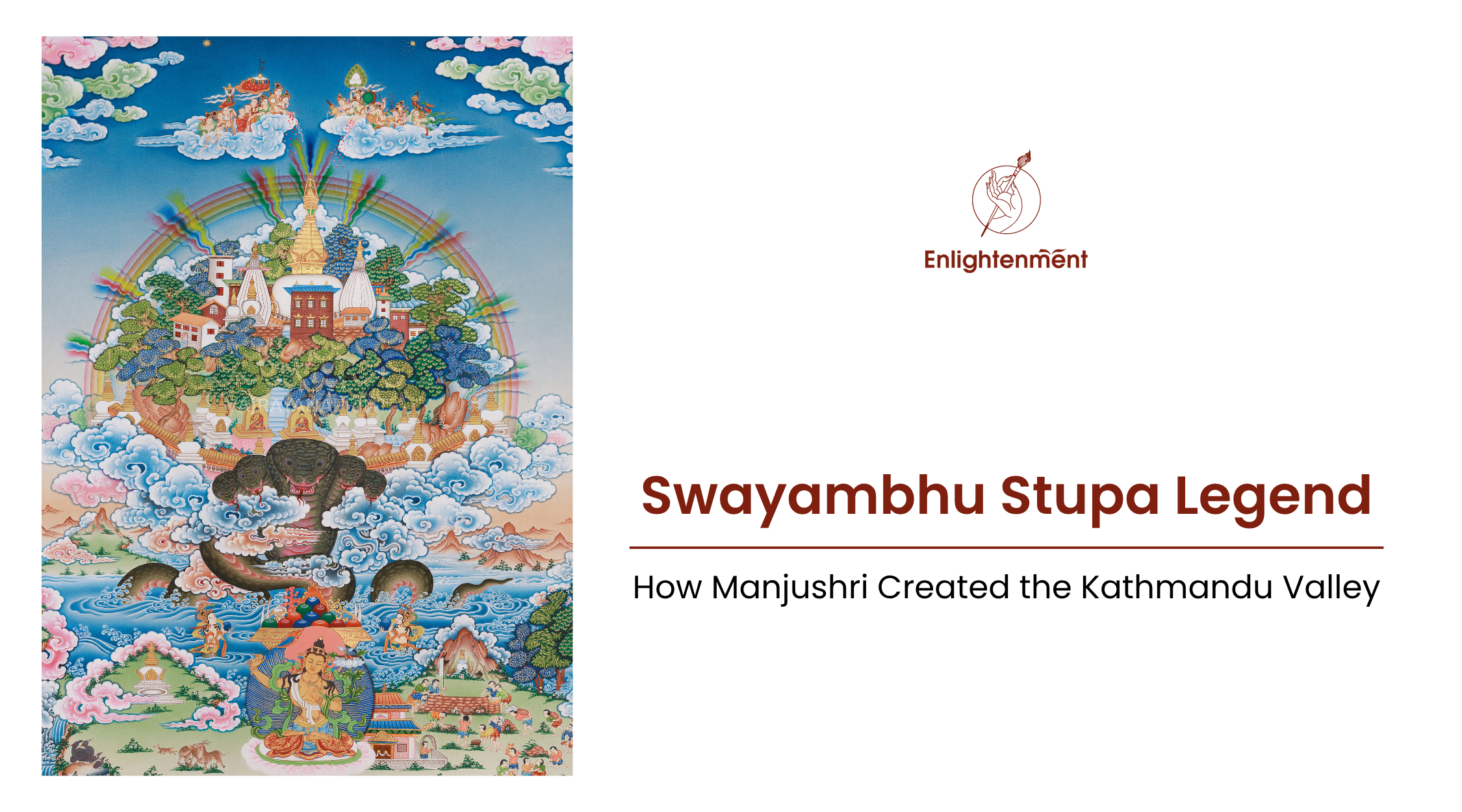

The legend of the Swayambhu Stupa, rooted in the Swayambhu Purāṇa, recounts the tale of Manjushri, the Bodhisattva of wisdom. He drained a massive lake to make the Kathmandu Valley livable. Following a vision of a brilliant lotus floating on the water, he used his sword to carve through the surrounding hills, letting the waters escape and unveiling the sacred ground where the Swayambhu Stupa now stands. This story is more than just a creation myth; it represents the victory of knowledge over ignorance and the transformation of nature into culture.

The residents of Kathmandu valley hold this tale in high regard, as it continues to shape religious practices, pilgrimage, and the Nepali identity, weaving together legend and landscape in a profound expression of spiritual heritage.

Earliest Texts: The Swayambhu Purāṇa

The Swayambhu Purāṇa (translated by Bajracharya in 1978) is a 15-chapter story that takes place across a huge cosmic timeline, starting from the ancient Satya Yuga (the first age of the world). It tells how seven Buddhas from the past—starting with Vipashyin and ending with Kashyapa—all come to worship a mysterious self-created flame of light (jyotirūpa) that rises from the middle of a sacred lake.

In Chapter 4, one of these Buddhas, Krakuchchhanda, plays a special role. He predicts that a wise figure named Manjushri will one day come, and he gives a blessing to the lotus flower that protects the sacred flame.

Set against the backdrop of an expansive cosmic timeline, the Swayambhu Purāṇa portrays the Kathmandu Valley as more than just a physical location; it’s a sacred space intricately linked to the spiritual journeys of ancient Buddhas. The emergence of the self-arising flame (jyotirūpa) from the heart of the lake symbolizes a timeless essence of enlightenment, attracting the Seven Past Buddhas to pay homage. In Chapter 4, we meet Krakuchchhanda Buddha, who sees the sacred potential of this site and predicts the arrival of Manjushri, the bearer of wisdom destined to unveil it to the world. His blessing of the lotus that cradles the flame underscores the site's holiness and sets the stage for a remarkable transformation—a divine act that alters the landscape and redefines the spiritual map of the Himalayas.

Key mythic geography preserved in the text:

-

Kālīhrada / Nāgahrada – the primordial lake.

-

Jamacho (Nagarjuna) Hill – lookout used by Vipashyin.

-

Manjushri Hill (Sarasvatī Pārvat) – smaller knoll west of today’s stupa where Sakyamuni later lectures on the legend.

-

Nagadaha / Taudaha – remnant ponds created for the displaced serpent‑spirits (nāgas).

Manjushri’s Pilgrimage from Mount Wutai

The artistic connections between Nepal and China stretch back at least to the 5th century, when Licchavi gilt bronzes were exchanged along the trans-Himalayan trade routes. However, the legends suggest an even deeper bond. According to the Swayambhu Purāṇa, the bodhisattva Manjushri leaves Mount Wutai in Shanxi, China, after receiving a divine vision of the Lotus Flame glowing from the heart of a vast lake in the Kathmandu Valley. Riding a majestic blue lion and accompanied by his tantric companions, Barāda and Makshadā, Manjushri journeys through Tibet, enters Nepal at Nyalam, and sets up camp for three nights on Mahamandap Giri, a hill to the east of Bhaktapur, to gaze upon the sacred lake and validate his vision.

Upon seeing the valley submerged, Manjushri resolves to make it livable for both humans and sages. With a single, fiery swing of his sword, the Candrahāsa, he cleaves open the valley rim at Chobhar Gorge, letting the lake’s turquoise waters surge into the Bagmati River. As the waters recede, the magnificent lotus that had held the eternal flame tips over and settles on a rocky hill—now known as Semgu or Singhu Hill, the future home of the Swayambhunath Stupa.

Aftermath: Nāgas, New Lakes, and the First King

As the waters recede, the serpent-deities, known as nāgas, find themselves displaced from their underwater homes, writhing in the drying lakebed. Witnessing their plight, Manjushri, filled with compassion, carves out a deep basin to the southwest of the Chobhar Gorge. This area transforms into Taudaha, a peaceful haven where the Nāga King Karkotaka and his family can find refuge, nurturing the age-old connection between humans and nature spirits.

With the valley now suitable for living, Manjushri sets his sights on building civilization. He lays down the groundwork for a new city, Manjupattana, on the newly formed river plains. Thoughtfully designed and established through rituals, it becomes the first human settlement in the Kathmandu Valley. To lead this new community, he chooses the wise and virtuous Dharmakara, a noble trader, as king—a pivotal moment that is later chronicled in the Gopāla-rāja-vaṃśāvalī, Nepal’s oldest royal record, which ties divine insight to the lineage of rulers.

Shantikar Acharya and the First Chaitya

Generations later, the tantric master Shantikar Ācārya, who was once a king of Gaur before embracing monastic life, finds himself troubled by the threat of wind and rain to the eternal flame. In his quest to protect this sacred light, he approaches Licchavi King Vṛṣadeva (who reigned around 400–550 CE) for financial support to encase the flame in brick and lime. An inscription discovered on the stupa’s north-west plinth credits Vṛṣadeva as the donor, marking this as one of the earliest dated Buddhist structures in Nepal.

Architecture of Swayambhu Stupa as Mandala

|

Element |

Nepali / Sanskrit Term |

Symbolic Meaning |

Field Notes |

|

White dome |

Anda |

World of saṃsāra |

Layers of clay mud‑mortar over brick. |

|

Square harmika |

Harmikā |

Abode of the gods |

Decorated with the famed Eyes of Wisdom. |

|

Central mast |

Yasti |

Axis mundi & Manjushri’s sword |

Capped by triple parasols (chatras). |

|

Thirteen gilt disks |

Chudāmaṇi |

13 bhūmis to enlightenment |

Re‑gilded with 20 kg gold in 2010. |

|

Umbrella & finial |

Gajur |

Buddhahood |

New repoussé panels added 2020–22. |

|

Four toranas |

Pradakṣiṇa‑dvāra |

Life events of Buddha: birth (E), awakening (S), first sermon (W), parinirvāṇa (N) |

Restored 2015 with Malla‑period bronzes. |

|

Vajra thunderbolt |

Dorje |

Indestructible truth |

3.2‑ton gilt‑bronze, visible at east stairhead. |

Western art historians often compare the plan to a Śrī Cakra mandala: the stupa is the bindu, satellite chaityas trace the petals, and the encircling promenade (pradakṣiṇa‑patha) functions as the outer square.

Living Rituals at Swayambhunath Stupa

1. Gunla Parva (Aug/Sep)

During the ninth lunar month, which the Newars call Gunla (or Gunla Bājan), the devoted bands from the Newar Buddhist community embark on early morning pilgrimages to Swayambhunath. These groups bring along traditional instruments like long brass horns (bhusya), tiny clay stupas, and scrolls of the Prajñāpāramitā scriptures, symbolizing the essence of wisdom.

This observance is deeply embedded in the Newar Vajrayana tradition, blending music, ritual, and the spirit of communal merit-making. In 2024, the event reached new heights with numerous devotees participating.

2. Losar & Buddha Jayanti

Every year during Losar, which is the Tibetan New Year, Gelugpa monks put on these incredible cham masked dances at the stupa. These performances are not just for show; they represent the victory of wisdom over ignorance. Then, on Buddha Jayanti, which falls on the full moon in May, the relic casket containing the eternal flame is carried in a solemn procession three times around the stupa, inviting pilgrims to join in a collective act of devotion.

The daily spiritual practices add even more depth to the atmosphere:

- Lighting butter lamps as offerings, which symbolize the light of wisdom.

- Spinning prayer wheels while walking clockwise along the sacred path, often accompanied by soft chanting.

- Feeding the resident rhesus macaques, a mindful act of compassion that’s done carefully to avoid overfeeding or disturbing their natural habits.

Through these rituals and everyday expressions of reverence, the site continues to be a profoundly meaningful place for embodying the values of Buddhism, especially compassion, mindfulness, and interdependence.

Conclusion

As the first light of dawn kisses the golden spire of Swayambhunath, the Eyes of Wisdom seem to awaken: quiet yet full of expression, watching over the valley below. Their gaze conveys a profound truth: that clarity, symbolized by Manjushri’s sword, and compassion, represented by the stupa’s dome, aren’t at odds with each other, but rather two sides of the same coin on the journey toward collective enlightenment.

The lasting allure of Swayambhu Stupa’s legend doesn’t rest on the literal image of a sword carving into stone, but rather on the way myth, landscape, and devotion weave together to create a vibrant mandala. In this sacred tapestry of stories and places, Kathmandu transforms from just a city into a mirror of our inner selves, where wisdom and compassion must rise hand in hand, time and time again, with the morning sun.

Glossary

-

Candrahāsa – “Moon‑laughing”, Manjushri’s sword.

-

Dorje – Vajra; thunderbolt symbol.

-

Gunla Bājan – Newar devotional music ensemble.

-

Jyotirūpa – Self‑manifest flame/light.

-

Nāga – Serpent deity linked to water and fertility.

Sources:

1. Mythological History of the Nepal Valley from the Swayambhu Purana. Bajracharya, Mana Bahadur, Avalok Publishers, 1978