The Fascination of Tibetan Anatomical Thangkas

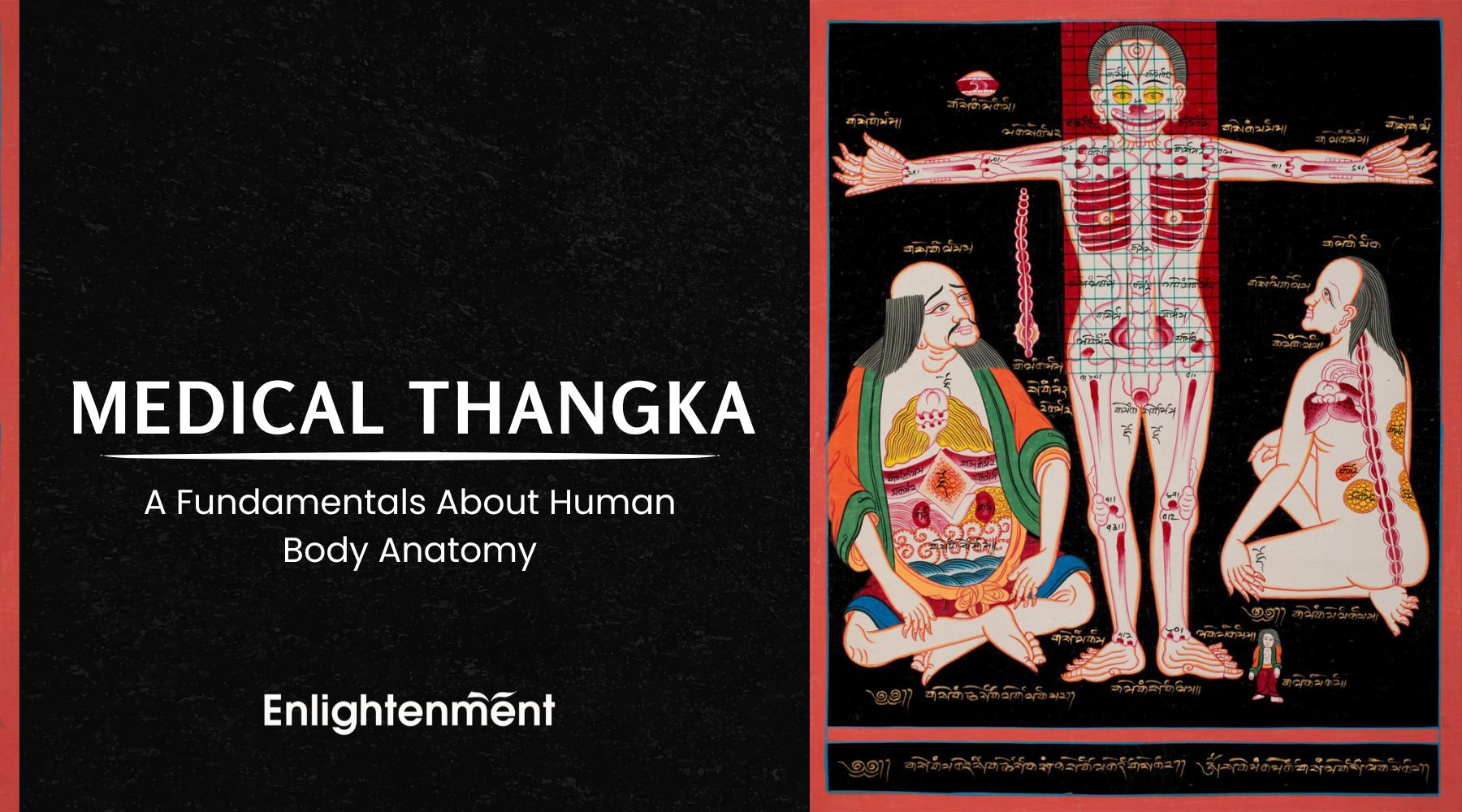

The world of anatomy has always held a deep intrigue for cultures across the globe, including Tibetan medical thangkas. In the context of Tibetan Buddhism, the depiction of the human body goes beyond physical structures, intertwining spiritual significance with anatomical details. The Tibetan thangka art, a centuries-old practice, provides an extraordinary visual narrative of the human body. This blog delves into the rich history, detailed symbolism, and educational value of the Tibetan anatomical thangka, especially those created in the 17th century. That is why the opinion about anatomical thangkas of Tibet is favorable, as being the examples of the combination of art, religious beliefs, and the advanced deposit of Tibetan medicine.

Unlike the Western anatomical charts that depict the human body from anatomical perspective, these thangkas depict the human body from a spiritual perspective, as adopted in the overall Tibetan Buddhism concept of being and existence. They illustrate the networks of subtle energy pathways between centres of energy and spiritual signs, stressing integration of the aspects of mind, body, and spirit. While they are beautiful works of art, anatomical thangkas are used for meditation, as diagnostic aids by Tibetan medicine practitioners, and are an embodiment of old Tibetan wisdom. The present tries to engage individuals fascinated with such things as integrative medicine and spirituality, among whole other subjects, and provide enthusiasts with a unique, symbolic view of the human body, thus linking artwork with philosophical concepts.

How Tibetan Anatomy Differed from Western Medical Knowledge

One remarkable aspect of the Tibetan anatomical thangkas is the distinction they drew in terms of bone count. Tibetan anatomists calculated 360 bones in the human body, considering elements like cartilage and even fingernails and toenails as part of the skeletal structure. This contrasts with the Western anatomical view, which recognizes 206 bones, excluding cartilage and nails.

Bones are grouped into twenty-three types and three hundred and sixty differently numbered bones. With regard to the former, there are active groups of cranial bones, including the cranium (thod-pa), the foramen magnum (Itag-pa), nasal bones and teeth, and the mandible (ma-mgal). The nine groups of bones in the trunk include vertebrae or bodies of the individual vertebrae (egal tshigs), vertebral transverse processes (byadab), coccyx, hip bones or bones of the womb or hollow of the back (dpyi-rus), shoulder blades or scapulae (sog-pa), collarbones, and bosom bones or bones of the breastbone (agrog-rua). Thus, arm bones can be divided into three categories: the upper arm, or humerus (dpung-thang), the forearm, including radius and ulna (rje-ngar), and the hand and the carpi, metacarpi, and phalanges (lag-mgeirus-pul). Five different groups of leg bones are there, such as the thighbone or femur; the lower leg includes the tibia and fibula; the kneecap or patella is also found; the heelbone or calcaneus is also included; and the other is the foot, including the tarsi, metatarsal, and phalanges, respectively; and finally, there is one grouped bone, which is the finger and toe nails.

The three hundred and sixty distinct bones are divided between these twenty-three groups as follows: Four maxillary bones, two on both sides of the lower jaw bones (fza-gram-pa), thirty two teeth, including wisdom teeth, thirty two dental roots, twenty bones behind the ear from the neck to the gullet (mid-pa), two ‘twin orbit’, eight occipital, two collar bones, two shoulder blades, thirty two back bones, including the five neck bones and first three tail bones (spine and coccy).

These include twelve major and two hundred and ten minor joints or articulations sufficiently conjoining all bones in the body. There are six limbs that make up the major joints, including the shoulders, elbows, wrists, hips, knees and ankles. The minor articulations include, for instance, articulation of fingers and toes, twenty-eight vertebral articulations and articulations of dental roots with the jawbone, and twenty bones linking the ear and the oesophagus.

We have sixteen tendons in our body, eight from the arms and legs. The former encases the joints of the elbows and wrists, and the latter encases the knee (hamstring) and ankles. There are four small tendons that attach to the vertebrate externally and internally; two are found in the neck; another two are funnelled to the inner ankles; those are to be cauterized for male impotence.

It is also important to note that the human skin has thirty-five million pores, and only seven million of them are situated on the upper half of the chest. Fourteen million are situated on the trunk; there are three and a half million per hand and leg.

There are five solid viscera, of which the first four are represented on this plate, namely the heart , lungs , liver , spleen, and kidneys. There are six hollow organs, including the stomach , small intestine , large intestine , gall bladder , urinary bladder, and the reservoir for reproductive fluid.

Establish the sectarian lineage of the Yuthog-pa school down to the period of Terdak Lingpa (1646-1714) with the help of principal Nyingmapa teachers of the hierarchs of the monasteries of Dorje Trak, inter alia. Chogyel Tashi Topgyel and Rikdzin Ngagiwangpo, and its branch monastery called Mindroling (et cetera). Terdak Lingpa himself. Kane H-Ngeng began tracing the drawing of the text, the bDud-rtsi bum-pa, which was transmitted through Bhaisajyaguru, three major Bodhisattvas, and Padmasambhava, as well as his immediate disciples who propagated this tradition in Tibet with him.

The interconnecting blood vessel channels

Click To View Tibetan Thangka Depicting the Circulation of Blood

Overall, the interconnecting channels are estimated at seventy-two thousand in significant tantra-texts like Kalacakra, according to the hermit sage Vidyajñana. However, there are four main categories in the medical tradition: the channels of existence (srid-pa'i rtsa), the channels of connection (brel-pa'i rtsa), the channels of embryonic formation (chags-pa'irtsa), and the course of the lifespan principle (tshe-gnas-pa'i rise). Of them, the routes of embryonic genesis, existence, and connections.

During the process of embryonic development, the channel of formation spreads downward to create the genitals, outward to create the black channel of life with its blood vessels, and upward from the navel to create the brain and its white channels. The three channels—the left channel and its branches (rkyang-ma), which conduct water; the right channel (ro-ma) and its branches, which transport blood; and the central channel beneath the navel (dbu-ma), which conducts wind—are especially mentioned in tantric literature in reference to this fundamental anatomy. Additionally, the heart is connected to pulsing channels that transmit wind and blood together. The crown, throat, heart, navel, and genitalia are the focal points or centers (cakra/rtsa-'khor) where these three fundamental channels are said to converge. From these points, they radiate outward in a network of twenty-four "spokes" (rtsa-'dab), or major channels, and five hundred minor channels. Generally speaking, the genitalia and wind are characterized as products of desire and the center energy channel, the brain and phlegm as products of illusion and the left energy channel, and the channel of life and bile as products of hatred and the right energy channel.

The right channel (ro-ma) creates the black channel of life that splits into blood vessels. It runs alongside the spine from the twelfth vertebra all the way to the manubrium. It is referred to as the source that keeps flesh and blood alive. Although blood vessels are generally divided into two categories: pulsating arteries ('phar-rtsa) and non-pulsating veins (sdad-rtsa). In total, there are twenty-four major blood vessels: sixteen external blood vessels that are connected to the head and limbs, and eight internal blood vessels that are connected to the solid and hollow viscera. The plate that follows shows the former. Regarding the latter, they include the two "Black Extremities" that are attached to the upper bifurcated extremities of the channel of life, the two cartoid arteries to the heart that cause unconsciousness when pressed, the two "extremities" that resemble the liver, and the four great vessels that split into the four limbs.

Overall, the interconnecting channels are estimated at seventy-two thousand in significant tantra-texts like Kalacakra, according to the hermit sage Vidyajñana. However, there are four main categories in the medical tradition: the channels of existence (srid-pa'i rtsa), the channels of connection (brel-pa'i rtsa), the channels of embryonic formation (chags-pa'irtsa), and the course of the lifespan principle (tshe-gnas-pa'i rise). Of them, the routes of embryonic genesis, existence, and connections.

During the process of embryonic development, the channel of formation spreads downward to create the genitals, outward to create the black channel of life with its blood vessels, and upward from the navel to create the brain and its white channels. The three channels—the left channel and its branches (rkyang-ma), which conduct water; the right channel (ro-ma) and its branches, which transport blood; and the central channel beneath the navel (dbu-ma), which conducts wind—are especially mentioned in tantric literature in reference to this fundamental anatomy. Additionally, the heart is connected to pulsing channels that transmit wind and blood together. The crown, throat, heart, navel, and genitalia are the focal points or centers (cakra/rtsa-'khor), where these three fundamental channels are said to converge. From these points, they radiate outward in a network of twenty-four "spokes" (rtsa-'dab), or major channels, and five hundred minor channels. Generally speaking, the genitalia and wind are characterized as products of desire and the center energy channel, the brain and phlegm as products of illusion and the left energy channel, and the channel of life and bile as products of hatred and the right energy channel.

The right channel (ro-ma) creates the black channel of life that splits into blood vessels. It runs alongside the spine from the twelfth vertebra all the way to the manubrium. It is referred to as the source that keeps flesh and blood alive. Although blood vessels are generally divided into two categories: pulsating arteries ('phar-rtsa) and non-pulsating veins (sdad-rtsa). In total, there are twenty-four major blood vessels: sixteen external blood vessels that are connected to the head and limbs, and eight internal blood vessels that are connected to the solid and hollow viscera. The plate that follows shows the former. Regarding the latter, they include the two "Black Extremities" that are attached to the upper bifurcated extremities of the channel of life, the two cartoid arteries to the heart that cause unconsciousness when pressed, the two "extremities" that resemble the liver, and the four great vessels that split into the four limbs.

The interconnecting channels in the body are entusrated at 722,000 in tantra texts like Kalacakra.

The medical tradition consists of four major categories: the channel of embryonic formation, existence, connection, and the course of the lifespan principle. Plate nine depicts the channels of embryonic formation, existence, and connection. The channel of formation extends from the navel to generate the brain and white channels, the black channel of life with blood vessels, and the genitals. The channels converge at focal points within the body, radiating outward in a series of 24 major channels and 5 hundred minor channels. The black channel of life, which divides into blood vessels, is generated from the right channel and adjoins the spine. There are 24 major blood vessels, eight internal and sixteen external, connected to the head and limbs.

Role of Thangkas in Tibetan Medical Education

Thangka art is closely associated with the medical science practiced in Tibetan Buddhism, not only as an article of faith but also as an instrument of instruction. These motifs are very detailed and frequently show organological and therapeutic aspects combined with religious elements, making it a very complex view of the concept of health. Energy, balance, and spirit are basic principles of traditional Tibetan medicine, and thangkas depict them by illustrating the body and its chakras, channels, and healing deities. Thus, entwined with the knowledge that Thangka art teaches the audience about physical and spiritual healing, Suchi is presenting an ancient idea of how people’s health centuries ago was closely connected to both realistic medical knowledge and spirituality.

Educational Techniques: Practical Learning Through Art

The vibrant colors and detailed illustrations in thangka art served as mnemonic devices, helping medical trainees remember complex information. By engaging with the art, students could visually connect symptoms with diagnoses and treatments, forming a complete mental map of Tibetan medical practices. Practical learning through art makes good learning-teaching method since learners are able to make practical movements in learning creatively. Through art, students increase their skills in approaches to learning such as critical analysis, perceptive, and interpretative abilities. For instance, art can be applied in areas such as history or science and can act as an anchor to make the principles much easier to understand. The practical approach used here creates a relationship between the learners and the material so that the learner applies knowledge instinctively. In summary, applying practical learning through art does help improve understanding further and definitely makes comprehension of subjects a happy one.

The Influence of Buddhist Philosophy in Anatomical Thangkas

In Tibetan medicine, the body is seen as an interconnected entity where physical ailments often reflect spiritual imbalances. The anatomical thangkas emphasize the balance of energies within the body, echoing Buddhist beliefs in harmony and interconnectedness. Diagnoses often incorporated both medical and spiritual observations, promoting a comprehensive treatment approach. The anatomy thangkas are incredibly rich in the heart of the Buddhist philosophy, as the enlightened beliefs are incorporated into depictions of the human form to produce something both instructive and inspiring. In these thangkas, the human body is depicted not only as a physical structure but as a number of energy channels, wheels, and spiritual paths, which is directly linked with Buddhist teachings concerning the interdependence of all elements and all processes. The purpose of this approach is to demonstrate the relationship between physical and spiritual health in the body-mind-spirit approach based on the Buddhist approach. These thangkas are used by practitioners to give a spiritual concept of health for meditation, healing, and self-enlightenment.

Modern Significance of Anatomical Thangkas

Today, thangkas are considered valuable cultural artifacts, with original paintings carefully preserved in monasteries and museums. They are treasured for their historical significance and unique representation of medical knowledge intertwined with Buddhist philosophy. Modern relevance of the anatomical thangkas is closing an educational gap and usefulness as meditative tools for practicing Tibetan medicine in the modern context. These thangkas depict the human anatomy together with emphasis on the energy channels, the chakras, and the other symbols of spiritual nature, which perhaps represent a reflection of the holistic system. Today, they promote modern practices of integrative medicine, which focus not only on people’s physical state. In art and in academic circles, anatomical thangkas get appreciated for their treatment of the depiction of anatomy and the traditional Buddhist concepts about it; thus, people can come to better understand the profundity of the Tibetan art, knowledge, and way of healing.

Relevance to Contemporary Alternative Medicine Practices

As interest in holistic and alternative medicine grows globally, Tibetan thangka art and traditional Tibetan medicine have gained renewed attention. The emphasis on balance, spiritual well-being, and alternative diagnostic methods resonates with current wellness trends, offering valuable insights for those exploring integrative health approaches. In terms of relevancy for modern specific kinds tertiary Complimentary and Alternative Medicine Tibetan anatomical Thangka paintings have a special implication in holistic and integrative medicine. In contrast with abstract and streamline anatomy charts, these thangkas focus on the movement of energy, harmony, and the interrelationship of physical, mental, and spiritual selves—concepts thriving in complementary and alternative medicine, such as acupuncture, Ayurveda, or energy therapy. In portraying the chakras, meridians, and energy channels, Thangkas provides the student of medical and health science with an understandable tool and guide for health in a holistic and integrated view. As many people turn to unconventional treatments, these thangkas help others value the roots and seek help through the use of thangkas in the healing process.

Detailed Breakdown of Key Anatomy Elements in Tibetan Thangkas

Click To View Human Anatomy Thangka

Colors in Tibetan thangka paintings serve as more than mere decoration. Each color has a specific meaning: red often represents life force and strength, while blue symbolizes tranquility and protection. These colors help depict organs and body parts in a way that aligns with Tibetan medicine, associating physical structures with spiritual attributes. For instance, the heart may be shown in red to signify both its physical function in circulation and its symbolic role as the seat of life energy.

The Role of Thangka in Tibetan Medicine Today

Although medical science has evolved considerably, Tibetan thangkas remain relevant. Modern practitioners of traditional Tibetan medicine still reference thangka art to understand the human body from a holistic perspective. Museums, universities, and alternative medicine practitioners around the world study these artworks to gain insight into traditional methods of diagnosis and healing, recognizing that Tibetan medicine offers unique approaches valuable to both historical understanding and contemporary wellness.

The principles embodied in Tibetan thangkas resonate with today’s emphasis on holistic health. The focus on balance, energy flow, and mental well-being aligns well with modern practices such as mindfulness and integrative medicine. Tibetan thangka art encourages us to see the body not just as a machine of interconnected systems but as an energetic entity that requires harmony on multiple levels for optimal health.

Preservation and Global Appreciation of Thangka Art

Today, Tibetan thangka art is recognized as a valuable part of cultural heritage. Efforts are being made to preserve these works in their original form. Museums and collectors prioritize the preservation of thangkas, ensuring future generations can appreciate these intricate artworks that represent centuries of wisdom and tradition.

Immediate measures should therefore be taken to keep Thangkas as cultural assets so that such historical and spiritual pieces of the Tibetan Buddhist art are not lost. Tang ka, or Thangkas, are painted scrolls that represent deities, Mandalas, or teachings of Buddhism that are painted using very fine methods inherited from ancestors. They are used in Buddhism practice as well as in teaching, and they also have historical importance. However, thangkas are threatened by natural conditions that affect them, the deterioration of material used, and at other times, a lack of conservation information.

Measures to preserve thangkas are storage in specific conditions to preserve them, teaching the master artisans of the traditional way, and popularizing them. Thangkas belong to museums, monasteries, or centers of any culture; efforts are made to preserve these paintings and exhibit them for their rightful prompt importance. Besides, digital archiving enables generations to come to experience such treasures of culture as traditional designs and details that may have been thrown to the converter. In protecting thangkas, a link to the past is sustained and sustenance given to a centuries-old tradition that forms the basis of Tibetan Buddhism and is a creative expression of religious and cultural faith.

Tibetan thangka anatomy has influenced not only Tibetan and Himalayan regions but has also inspired Western artists, spiritual leaders, and medical practitioners interested in holistic health. This cross-cultural appreciation highlights how ancient art can bridge historical knowledge with modern wellness approaches, fostering a global understanding of health and spirituality.

The History and Tradition of the Anatomical Thangkas of Tibet

The anatomical thangkas of Tibet help people today to look into a previous more global vision of health and where it connects with the spirit. The feelings, their oneness with the figures, the vivid colors, the individuality, and profound meaning are all significant as well and tell us it is not only about the physical. These artworks embody a cosmology that balances and integrates polarities, perceives holons, and respects creation; thus, Tibetan thangka anatomy is an ever-valuable resource for both linear historical studies and cyclic contemporary interpretation.

Therefore, this blog sought to establish that the conventional wisdom found in the Tibetan anatomical thangkas cannot only be attributed to the canonical art and religion of the Tibetan Buddhist culture, but it is also heavily infused with the older form of medical wisdom as well. These thangka registered traditional knowledge and culture, which depicted the physical form of a human with energy channels and related spirituality that is congruent to Tibetan Buddhism for hundreds of generations. They remain useful for art and scholars, playing a decisive role in promoting the needs of a creative and healthy body and soul within an individual. In as much as these anatomical thangkas represent the integrated welfare of human beings today, they still share great value in contemporary society as they help to bring about a different perception of knowing the body, besides enhancing a rich understanding of the Tibetan culture. This legacy is about the potential of art in showing people around the world a connection to the present, as well as the ancient and holistic ways of understanding ourselves.