Sitatapatra, Invincible Mother with a Thousand Heads and Hands

Pronounced as See-tah-tah-pah-TRAH, she is as an invincible protector against every form of supernatural danger, such as demons, black magic, and astrologically ordained mishaps.

The parasol after which she is named is not an ordinary umbrella but a large, white silken canopy that serves as a symbol of a high rank— a sign of royalty and divinity.

I salute you, exalted one!

Only mother of all Buddhas, past, present, and future,

Your glory pervades the three worlds.

Homage to you, savioress from the evil influence of demons

and planets,

From untimely death and evil dreams,

From the dangers of poison, arms, fire, and water.

The mandala of your being is exceedingly vast.

You have a thousand heads full of innumerable mindstates,

A thousand hands holding flaming attributes.

Queen of all the mandalas of the three worlds . ..

Ever-present in the work of taming evil ones,

I salute you, goddess of magical spells, turning demons into dust!

—Gelug ritual prayer

As an emblem of kingship, the white umbrella shelters the ruler from the sun’s rays. With which he must never come into direct contact lest they diminish his own luster. The parasol proclaims the spiritual sovereignty of the Buddha and his dominion over all worldly appearances and suffering.

Sitatapatra’s delicate beauty belies her indomitability. Moreover, she represents an invincible force. The method of invoking her is relatively simple. It is a fortuitous combination that has commended her practice to Buddhists throughout Asia and established her in the repertoire of every Tibetan Buddhist sect.

The Mythic Association of Sitatapatra and the Royal Umbrella

According to the Buddhist origin account, Shakyamuni Buddha materialized the goddess from the crown of his head (Ushnisa, “crown protrusion” ) when he was in Trayastrim Sa Heaven. The Buddha entered a meditative state known as “Perfect vision of the diadem ” and emitted the holy syllables of her dharani in the form of letters etched in light.

Next her voice was heard, greeting Buddha and assembled bodhisattvas, deities, and spirits. Finally, the light of the Buddha’s mind, streaming from the top of his head, crystallized into the sparkling white body and sunshade of Sitatapatra.

The Buddha pronounced her role to be “to cut asunder completely all malignant demons, to cut asunder all the spells of others, to turn aside all enemies and dangers and hatred.”

To prevent her seraphic persona to mislead the congregation, he asserted that "Sitatapatra is a fierce, terrifying goddess, garlanded by flames, a pulverizer of enemies and demons, who manifests in the form of a graceful, beauteous maiden". This is reflected in a longer version of her name, Usnisasitatapatra, which means “White Parasol Lady Who Emerged from the Buddha’s Crown of Light”. The origin story does not address her relationship to the Buddha’s sunshade.

Only her name evinces her personification of the saving energy inherent in the white (sita), parasol (atapatra), while the story traces the source of this energy to Buddha’s cosmic awareness and supernal brilliance. Sitatapatra represents a Mahayana version of a figural type already present in Buddhist mythology, a female spirit that indwells a royal parasol and acts as a royal patron.

1. The Mahaunmagga Jataka :

This story recounts Buddha’s former life as Prince Mahosadha, and her as a pivotal character, the goddess who “dwelt in the royal parasol.”

One night she emerged from the center of the parasol and posed four riddles to the king. When the foremost wise men in the realm could not solve the riddles, the goddess enraged and threatened that if the king did not produce the answers she would sever his head with her “fiery blade.” She scolded him for seeking out the famous wise men but overlooking his own son Mahosadha and said:

“What do they know? Like fireflies are they, like a great flaming fire is Mahosadha blazing with wisdom. If you do not find out this question, you are a dead man”.

Prince Mahosadha, who had been wandering in self-imposed exile, was promptly summoned to the palace. The king accorded his son the honor of sitting on the throne in the shade of the white parasol. Mahosadha reassured his father:

“Sire, be it the deity of the White Parasol, or be they the four great kings, let who will ask a question and I will answer it.”

When Mahosadha solved the first riddle, the goddess rose from the parasol. Revealing the upper half of her body, and rewarded him with a casket of heavenly perfumes and flowers. She praised him in the sweet tones. As he unraveled each successive riddles, she emerged and presented him with scent and blossoms. When he solved the final riddle, she gifted him with coral, ivory, and other precious objects befitting a king. Mahosadha remained at the palace and proceeded to restore order to the kingdom. He revealed treasonous plots and advising the king how to repel an invasion. Thus, it transpired that the goddess’s riddles had been a stratagem to bring Mahosadha to his father’s assistance and establish the security of the realm.

Interestingly, the story also uses “white umbrella’’ as a metaphor for royal protection. When the prince announces, “I am indeed the king’s white umbrella,” in reference to his success in securing the safety of the throne.

2. The Mugapakkha Jataka:

In this former life, the Buddha-to-be decided in infancy that he did not want to assume the throne when he grew older. The king was an unrighteous ruler. And the Bodhisattva feared that he would collect negative karma if he followed in his father’s footsteps. The goddess of the white parasol under which the princeling was shaded advised that he could escape this fate if he pretended to be deaf and showed no signs of intelligence.

He followed her advice, feigning an inability to rule for sixteen years, until he was finally released to pursue a life of asceticism as a forest hermit. Inspired by his example, the king and queen decided to become ascetics themselves and attempted to relinquish the throne and royal umbrella to the Bodhisattva.

The Bodhisattva’s indifference to worldly sovereignty inspired everyone in the realm to embrace renunciation. An invading ruler from an adjoining territory was similarly converted and withdrew his troops. The intervention of the parasol goddess benefited the royal family and kingdom at large.

The “white parasol goddess” is not a single figure but rather a genre of goddesses believed to inhabit royal umbrellas. She is associated with sovereignty. She intercedes to protect and preserve the possessor of the honorary umbrella. Just as the umbrella itself shelters the ruler from harsh sunlight, the deity inhabiting the protective canopy would be a guardian figure who safeguards his reign. Thus, these narratives reveal the idea underlying the personification of the Buddha’s sunshade as a female deity.

Like her Mahayana counterpart, she is envisioned as a benevolent figure with a dulcet voice. Who manifests a wrathful demeanor and wields a sword when occasion demands. She inherited from her mythic prototype her association with the royal umbrella, protective function, and beatific yet fearsome nature.

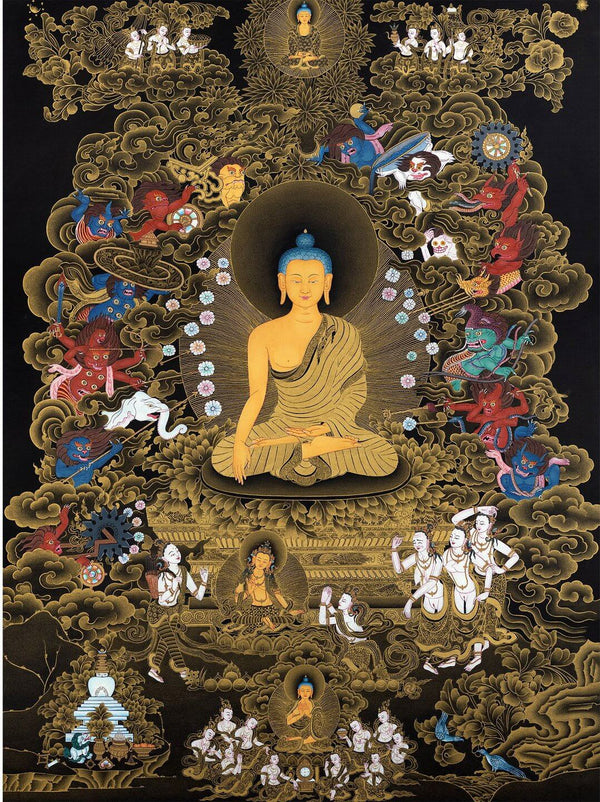

Her Thousand Fold Iconography:

The thousand-fold form of Sitatapatra is depicted in Tibetan art. Five colors of heads are shown in a tower-like formation. Each head has three eyes and each head has different expressions (tranquil, angry, or mirthful) as occasion demands to perform her activities.

The central face like her body is white. Her hands, arranged in concentric layers, form a fanlike aureole. Distributed among them are her implements and weapons such as: Vajras, Dharma-wheels, jewels, lotuses, swords, bows, arrows, lassos, goads, and crossed vajras. Each hand has an open eye on its palm to symbolize the omniscience that guides her movements.

The following song of praise, delineates her thousand fold iconography:

Born from the crown protrusion of the Buddha, out of compassion,

You combat those who would harm the Buddhist teachings, the source of happiness,

And bestow the fruit of well-being;

I praise and pay homage to you, supremely blissful Sitatapatra.

Displaying many sacred gestures, such as granting refuge;

Holding scepters, wheels, jewels, lotuses,

Swords, arrows, bows, and lassos,

I pay homage to you, with your thousand arms.Your body is white, red, blue, yellow, and green;

You are graceful, heroic, and terrifying;

You appear tranquil, angry, and mirthful;

I pay homage to you, lady with a thousand heads.On your multiform body, with your many heads and arms,

Your wide-open eyes look to the sides,

Flashing with lightning like anger.

Homage to you, lady with a hundred thousand million eyes.

Your body is unbreakable as diamond,

Flaming like a mountain of apocalyptic fire,

Destroying all obstacles, bestowing all miraculous powers,

I pay homage to you, blazing, indestructible.

Source: Buddhist Goddess of India, Miranda Shaw